Agents of Change

For the past decade, the Global Women’s Institute has helped build the evidence base on violence against women and girls and what works to prevent gender-based violence.

Where does it go from here?

Story // Kathleen Garrigan

When fighting broke out in Juba, South Sudan, in July 2016, a research team trained by GW’s Global Women’s Institute was in the middle of collecting data on violence against women and girls (VAWG).

The work, led by the institute and its humanitarian partners, was part of the first large-scale, population-based study on VAWG in a conflict setting.

“We had pretty good methods for doing this kind of research in non-conflict circumstances, and we’d done some research in postconflict settings,” says Mary Ellsberg, founding director of the Global Women’s Institute (GWI). “But we needed to figure out how to adapt and apply that rigorous scientific method to an area that was in complete upheaval. There was some skepticism about whether it could even be done.”

As violence erupted, GWI and its partners were forced to pause the study. After six months, the study resumed but with some modifications: Previously the team had conducted door-to-door interviews at three sites, but one of those sites was deemed too challenging to proceed.

“The team felt it would threaten the data collectors’ security going door to door in Juba,” says Maureen Murphy, a research scientist with GWI who helped lead the South Sudan study alongside Ellsberg. “By pausing the study during the worst of the crisis, we were able to collect rigorous data without endangering the team on the ground.”

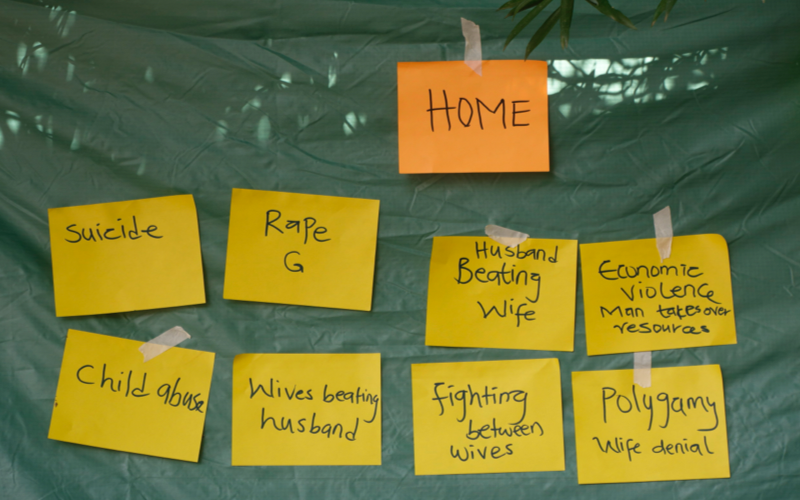

A key element in the study was its scope: Rather than focusing on rape and sexual violence perpetrated by soldiers, the team would be examining all forms of gender-based violence.

“We’ve known for a long time that rape is sometimes used by armed actors as a tactic of war,” Ellsberg says. “But there are other forms of violence—for example, intimate partner violence and forced marriages—that also occur or increase during war. Part of what we were trying to break down is this paradigm that conflict-related sexual violence is something that the U.N. should be doing something about, yet nobody’s paying any attention to what’s happening to women in their homes. Who are we to say which of those is worse?”

The findings from the team’s groundbreaking study—that as many as 73% of women had been physically or sexually assaulted by a partner, and one in three women had been sexually abused by a non-partner—completely upended the understanding about VAWG in conflict zones.

Not only were the findings revolutionary, but the methods and tools the team developed and adapted along the way created a global standard for the ethical and rigorous collection of VAWG data against a backdrop of volatility and uncertainty.

Today, the South Sudan study is representative of the pioneering work GWI has undertaken in 10 short years to fulfill its mission of advancing gender equality through research, education and action. Further evidence: GWI earlier this year was tapped to co-lead a new £65.7 million ($82 million) initiative to identify, evaluate and scale interventions that prevent VAWG around the world.

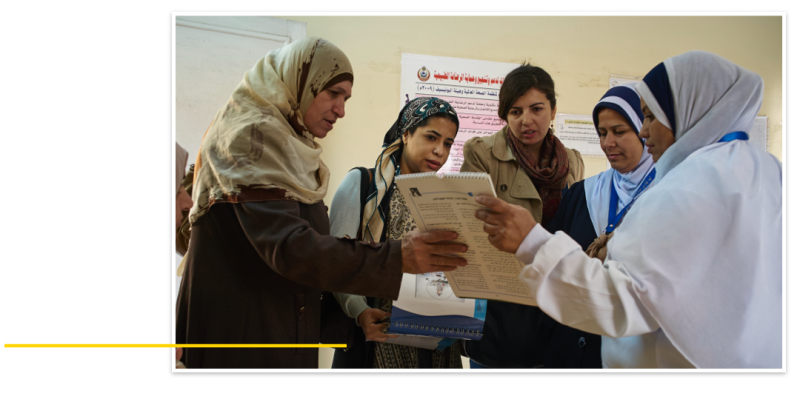

In South Sudan, GWI and its partners interviewed and led focus group discussions with community members, local leaders, survivors of VAWG and others.

Credit: GWI/Mary Ellsberg

Identifying different types of gender-based violence in the home.

Credit: GWI/Mary Ellsberg

Mary Ellsberg (left) on the ground in South Sudan with study partners.

Credit: GWI/Mary Ellsberg

Thirty years ago, there was scant evidence on VAWG’s prevalence and no standard practice for collecting data on it.

“There was almost no research on violence against women, particularly epidemiological research, until the 1990s when a few groups of feminist researchers around the world started trying to break that open,” Ellsberg says. She was one of those researchers.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Ellsberg was living and working in Nicaragua, where she was also a part of the country’s burgeoning women’s movement. In the early 1990s, members of the movement proposed a law criminalizing domestic violence. When government officials refused to vote on the law on the grounds that there was no evidence domestic violence was a problem, Ellsberg decided to get the numbers.

While pursuing a doctoral degree in epidemiology at Umeå University in Sweden, Ellsberg carried out the first population-based survey on domestic violence in Nicaragua in 1995.

“We had to make the case that violence was actually a public health issue, and that meant prevalence studies,” she says. “But that also meant developing methods for collecting data that were ethical and kept women safe.”

Over six months, Ellsberg and a research team that included members of the Nicaraguan women’s movement interviewed 488 women in León, Nicaragua’s second largest city, about their experiences with domestic abuse. When they published their study, the findings caused an uproar.

One out of every two women had experienced physical or sexual abuse by an intimate partner, and, of those, one in four women had experienced violence within the past year.

Feminist activists immediately launched a campaign to publicize the results of the study across radio, television and newspapers. Within six months, Nicaragua’s National Assembly unanimously passed the country’s first domestic violence law. Other legislative reforms and improvements in social and law enforcement services followed over the next couple of decades.

“Through this research we were able to uncover a devastating problem affecting Nicaraguan women that had been hidden for so long,” Ellsberg says. “At the same time, by partnering with the feminist movement throughout the research process, we were able to use our results to contribute to real social change.”

“There was almost no research on violence against women, particularly epidemiological research, until the 1990s when a few groups of feminist researchers around the world started trying to break that open.”

-Mary Ellsberg, GWI Founding Director

By this point, researchers around the world had been conducting similar studies. And in 2000, a landmark, multi-country World Health Organization study, which Ellsberg contributed to, revealed the enormity of the issue: Globally, one in three women would experience physical or sexual abuse in her lifetime. Ellsberg and other researchers also began collecting prevalence data that linked domestic violence to a range of medical conditions, including preeclampsia, depression, chronic pain, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome and heart disease.

“As the evidence accumulates, nobody can say, ‘This is not a human rights issue,’” Ellsberg says. “We have shown that violence against women and girls is both a violation of human rights as well as a health emergency.”

Twelve years later, Ellsberg came to The George Washington University. As the founding director of GWI, Ellsberg was able to draw on the work she did in Nicaragua and with the WHO to advance research on VAWG and its prevention around the world.

Early on, Ellsberg and her fledgling team were clear that their goal was to utilize their research to develop practical interventions that would improve the lives of women and girls.

“How can we be a partner who doesn't just care about doing academic research that ends up in peer-reviewed journals?” Ellsberg recalls the team discussing. “How do we become a center that is known for practical, policy-based solutions that can contribute to international dialogue at the [United Nations’] Commission on the Status of Women?”

Over the next 10 years, GWI would answer those questions.

One of the many revelations of the South Sudan study was that VAWG takes many forms and its perpetrators wear many faces. While one in three women in conflict settings reported sexual violence by a non-partner (a high rate when compared to non-conflict settings), the rate of intimate partner violence was even higher. Between 54% and 73% of women experienced sexual or physical violence by a partner.

In addition, the study revealed that humanitarian actors were sometimes reported as perpetrators of sexual abuse, and approximately 20% of women and girls reported being sexually exploited when they tried to access goods and services.

“It’s about power imbalances,” says Murphy, who now leads GWI’s Building Gender-Based Violence (GBV) Evidence in Conflict and Refugee Settings program, among other projects funded by the U.S. State Department. “In a humanitarian emergency, some of those power dynamics become more acute, and people become even more vulnerable because of that.”

For Amal Hassan, the fact that humanitarian actors were exploiting women and girls was shocking.

Hassan, a graduate research assistant with GWI who earned a bachelor’s degree from GW’s Milken Institute School of Public Health in 2022, joined the institute in 2019. As an undergraduate research intern, she began working with GWI’s Empowered Aid program, a participatory action research project studying sexual exploitation and abuse of women and girls in refugee settings in Lebanon and Uganda.

“I think one of the main things that surprised me was that most of the perpetrators of violence against women and girls in humanitarian settings were actually trusted people such as humanitarian aid workers,” she says. “They were workers who were supposed to be helping and distributing aid in a very diligent and honest way. There were also male community leaders and community activists and even relatives who were exploiting women and girls.”

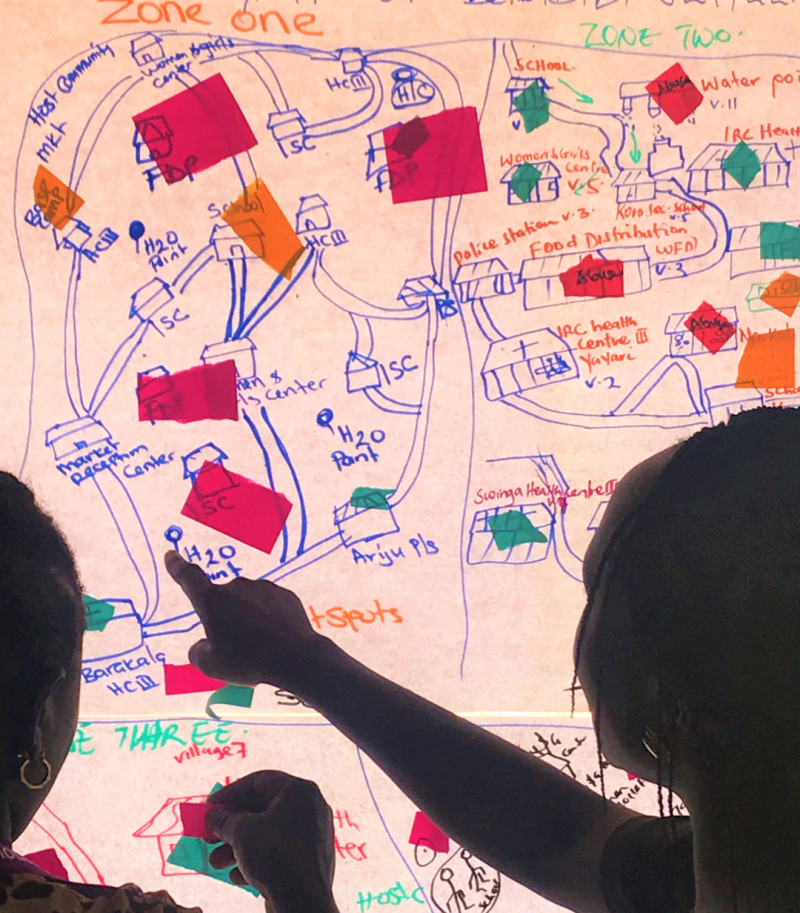

Working alongside refugee co-researchers in Uganda and Lebanon, Empowered Aid helped uncover a number of risks women and girls faced through aid distribution processes.

GWI recognizes women and girls as experts in contextual safeguarding. Here, women in Uganda and Lebanon identify safe and unsafe places in their communities through a community mapping exercise. Credit: GWI/Empowered Aid

In Lebanon, for example, where the majority of the country’s 870,000 refugees come from Syria, the Empowered Aid team found that women and girls’ were at an increased risk of sexual exploitation and abuse by sanitation and hygiene humanitarian workers who visited homes to make repairs. In Uganda, where people fleeing the conflict in South Sudan make up a large percentage of the country’s refugees, the team found that food distribution posed one of the greatest risks.

The team developed a series of recommendations, toolkits and even a free online course to help the humanitarian sector better mitigate sexual exploitation and abuse through aid distribution, monitoring and evaluation.

“That experience really changed my outlook,” says Hassan. “That the recommendations we came up with directly impacted women and girls in those contexts and allowed them to get humanitarian aid in a much safer way was extremely touching and empowering. It helped show that the work I was doing as an undergraduate research intern was really helping make a difference for this global public health crisis.”

The opportunities that GW students like Hassan have working at an institute like GWI are critical for the future of the field, says Murphy.

“We have a really strong commitment to students,” she says. “We’ve brought on a bunch of students over the years to work on research projects, which is exciting. That opportunity of working with researchers and the communities is important in building up the next generation of researchers and practitioners in the nongovernmental organization space.”

“That the recommendations we came up with directly impacted women and girls in those contexts and allowed them to get humanitarian aid in a much safer way was extremely touching and empowering. It helped show that the work I was doing as an undergraduate research intern was really helping make a difference for this global public health crisis.”

- Amal Hassan, GWI Graduate Research Assistant

Not long after GWI opened its doors, the institute published a review paper in a special issue of “The Lancet” medical journal focused on VAWG. They looked at all the rigorous studies aimed at reducing violence against women and girls and found that almost all of them focused on responses to violence. There was virtually no evidence as to whether the programs actually worked to prevent violence, and there were very few studies carried out in low- and middle-income countries.

Yet, violence could be prevented. Ellsberg showed that when she returned to Nicaragua in 2015 to carry out a follow-up study to her 1995 prevalence study. The study, published in “BMJ Global Health,” showed a 70% decline in physical intimate partner violence over a 20-year period. They attributed the decline to the success of the women’s movement and its ability to not only change laws and offer services for survivors, but also to transform gender norms and educate women about their human rights.

According to Chelsea Ullman, a research scientist who's been with GWI since its inception, the fact that violence is preventable has been one of the breakthroughs over the last 10 to 15 years.

“Not only is it preventable, but we can see reductions in violence within relatively short programmatic timeframes,” Ullman says. “I think we assumed that entrenched social norms that promote violence and gender inequality would take generations to change, that there’s no way you could meaningfully impact the rate of violence within a two-to-five-year program. But you can.”

We’re learning more every day about what works to prevent violence, Ullman says. She points to programs like Uganda’s SASA! Initiative, which engages all members of a community, including religious leaders, parents and children, as examples of effective prevention programming.

Created by the nonprofit organization Raising Voices, SASA!—meaning “Now!” in Kiswahili—focuses on the power imbalances between men and women.

“I think we assumed that entrenched social norms that promote violence and gender inequality would take generations to change, that there’s no way you could meaningfully impact the rate of violence within a two-to-five-year program. But you can.”

- Chelsea Ullman, GWI Research Scientist

“They don’t start by talking about violence,” Ullman says. “Some people are immediately turned off when you start talking about violence. But if you start by talking about how we all have power, and we all understand what it feels like to be without power, then we all have a choice about how we use our power.”

An evaluation of SASA! showed that the program reduces intimate partner violence by over 50%. Now the model has been adapted to other countries, including Haiti, where a GWI evaluation of a program in the southeast of the country found similar success in a different context.

“SASA! looks at violence prevention in a brand-new way, which is really about changing social norms and changing power imbalances,” Ellsberg says.

Claudia García-Moreno, who leads the WHO’s unit on vulnerable populations in the Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research and is a member of GW’s Leadership Council, has been witness to the institute’s meteoritic rise and impact over the last decade.

“GWI has made invaluable contributions to the field of violence against women, from research on the prevalence of violence against women in humanitarian settings to advocacy for prevention and services, including for migrant women, Indigenous women, political prisoners and other disadvantaged groups of women,” she says.

Earlier this year, GWI was selected to lead the Research and Evaluation Consortium of the “What Works to Prevent Violence Against Women and Girls: Impact at Scale.” Funded by the UK government, the seven-year, £65.7 million ($82 million) initiative is the world’s largest ever, multi-year global program to identify, scale up and evaluate measures to prevent gender-based violence.

When GWI conducted the South Sudan study in 2016, it was part of the first iteration of the “What Works” initiative. Now it leads one of the program’s two consortia.

“This is one tangible metric of our growth,” says Ullman, who is the deputy director of the “What Works” program. “The South Sudan study was innovative and new, and we were able to learn a lot in the field from it. That put us in a position where now, instead of taking one piece of the project, we’re able to help lead it.”

In partnership with research colleagues in Kenya, South Africa, Pakistan, Australia and the U.S, GWI will lead and support over 50 studies in dozens of countries over the next seven years. First, it will assess where information gaps still exist and where more research is needed, particularly in low- and middle-income countries and among populations with diverse identities.

“Many people have overlapping identities and some of those confer privilege and some of them don’t,” Ellsberg says. “We can’t just talk about ‘all women.’ We have to understand class, ethnicity, gender identity and sexual orientation. The dialogue and our understanding of gender has become so much richer with an intersectional lens.”

“GWI has made invaluable contributions to the field of violence against women, from research on the prevalence of violence against women in humanitarian settings to advocacy for prevention and services.”

-Claudia García-Moreno, World Health Organization

Beyond “What Works,” GWI continues to build capacity among humanitarian actors through its Building GBV Evidence and Empowered Aid programs. It is also preparing a new generation of global leaders through GenderPro, a credentialing program that trains mid- and senior-level development professionals to integrate gender into their work. The institute is also applying the lessons it has learned overseas to its own backyard.

“In the U.S., people are much less focused on prevention, and we think the work of groups like SASA! in Uganda and the work around changing social norms has a lot to teach people in the U.S.,” Ellsberg says.

As the U.S. Justice and State Departments develop gender-based violence action plans, for example, the institute has organized listening sessions between U.S. officials and global gender-based violence experts to share lessons learned from other countries.

For Ullman, the issue of VAWG in the U.S. is not so different from VAWG elsewhere. Different variables may exacerbate or change the way violence looks, she notes, but the intimate partner violence we see in South Sudan is the same type of violence we have here in the U.S.

“Violence happens everywhere,” Ullman says. “It varies by region, but there is no region in the world where it’s zero. However, this is an exciting moment, because we’re not only furthering our global knowledge but also building momentum to take action on VAWG.”

That momentum was on full display March 9 at an event to celebrate GWI’s 10-Year anniversary, where U.S. Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.) delivered the keynote address, calling GWI “an important catalytic force.

“You showed the world what it looks like to stop gender-based violence and, crucially, how to achieve that change,” she said. “And research that’s generated here actually does play a direct role in crafting stronger evidence-based policies and preparing the next generation of leaders to create an even stronger movement.”

A DECADE OF IMPACT

The Global Women’s Institute launches

The George Washington University establishes GWI, a pan-university initiative with Mary Ellsberg as founding director.

Partnering with the Malala Fund

GWI works with the Malala Fund to create a resource guide for universities and secondary schools based on the inspiring memoir by Nobel Prize winner Malala Yousafzai.

Spotlighting VAWG in The Lancet

GWI publishes a groundbreaking, comprehensive review of evidence-based interventions to prevent violence against women and girls (VAWG) in “The Lancet” in a first-ever issue focused on VAWG.

Pioneering research in South Sudan

GWI launches the first population-based study on VAWG in conflict-affected areas of South Sudan, which subsequently influences peace negotiations.

Documenting success in Nicaragua

GWI conducts a 20-year follow-up study to previous research in Nicaragua and finds a 70% reduction in intimate partner violence, demonstrating VAWG can be prevented through a multi-sector approach and feminist organizing.

Improving foreign assistance

GWI assesses the Australian government’s international program to end VAWG, evaluating the impact of investments to improve women’s access to justice, services, and prevention.

Training development professionals

GWI launches GenderPro, a first-of-its-kind program—delivered virtually and available globally —to professionalize, standardize and strengthen the field of gender within international development.

Evaluating programs to prevent VAWG

Between 2019 and 2022, GWI evaluates the Rethinking Power Program, developed by Beyond Borders and Raising Voices, in southeast Haiti. The program is now a proven solution that has reduced intimate partner violence by nearly 45%.

Stopping exploitation in refugee settings

GWI develops and leads Empowered Aid, a multi-year, multi-country project that explores sexual exploitation and abuse of women and girls in refugee settings, including Lebanon and Uganda.

Leading a global research consortium into the next decade

GWI is selected to lead the world’s largest ever, multi-year, global research consortium to study and scale effective measures to prevent gender-based violence through “What Works to Prevent Violence against Women and Girls: Impact at Scale,” a program funded by the UK government.

GWI celebrates 10 years

GWI celebrates the institute's first decade in action at GW and honors U.S. Rep. Pramila Jayapal, 33 ex-political prisoners from Nicaragua, and a sexual violence survivor and activist from Bolivia with Champions for Justice awards.

Called “Seven Sisters,” this painting by Shirleen Nampaynpa Campbell, an Indigenous women’s rights activist and artist from Australia, was commissioned by GWI.

“The story of the seven sisters is found all around the world and has been spoken in different ways and forms. It says that we all come from Mother Earth and her womb. It is about the strength and resilience of women and says that we are sisters all across the world.”

- Shirleen Nampaynpa Campbell