Closing the Healing Gap

Researchers at the GW Center for Global Mental Health Equity are working to treat mental illnesses and reduce mental health stigma in settings from Uganda and Nepal to New York City.

Story // Sarah C.P. Williams

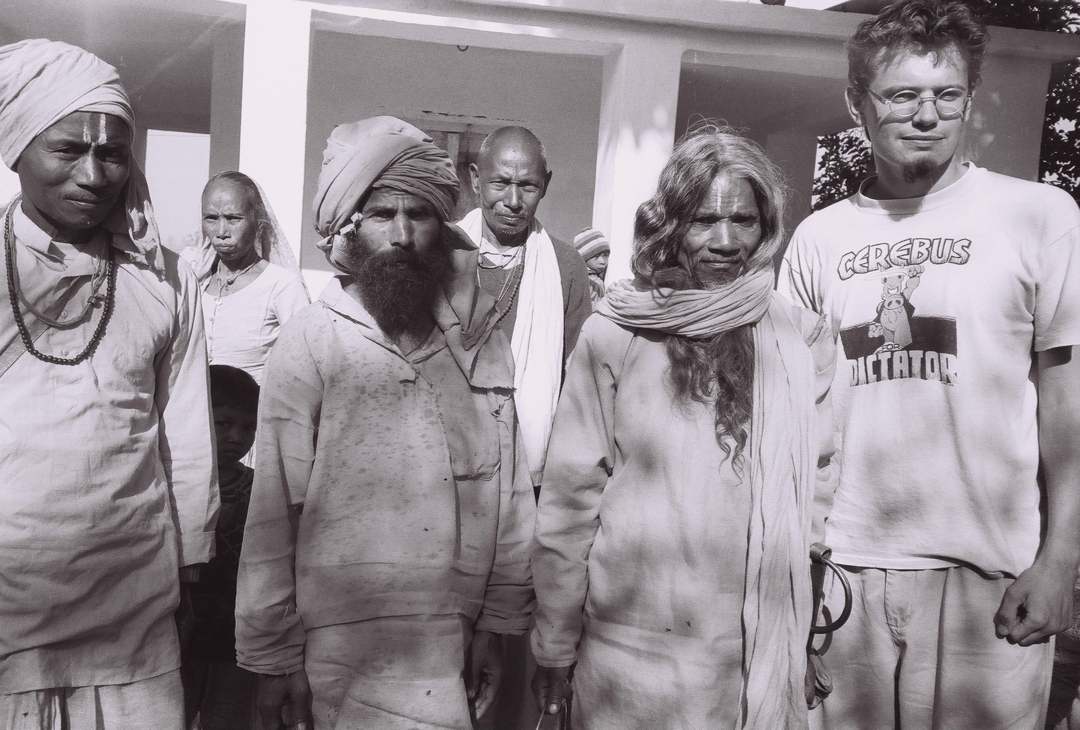

The first time he went to Nepal, Brandon Kohrt was an undergraduate film and anthropology student.

It was the late 1990s, and the Communist Party of Nepal had recently launched a war against the country’s monarchy and ruling political parties. Kohrt, who co-wrote an award-winning documentary on Nepal’s child soldiers, spent several months at a small traditional healing temple in rural southeastern Nepal. There, he was struck by the extent of mental anguish among the people coming to the temple—many were struggling with severe mental illnesses and had been brought there by their families.

“It became hard for me to just document the challenges and suffering I saw and not in some way contribute to the alleviation of that suffering,” recalls Kohrt. “I began to think that if I was going to bear witness to how people get through really difficult situations around the world, I wanted to be able to contribute in a more meaningful way.”

Something else caught his attention too: the degree to which the temple’s priests could ease people’s suffering through simple conversations and rituals. Every morning, people would arrive to speak with the holy men, who patiently listened to their worries, offering words of advice and light touches with feathers. Visitors seemed to leave happier.

Kohrt (right) with local priests at a healing temple in Nepal in the late 1990s.

Kohrt, who went on to earn both a Ph.D. in medical anthropology and an M.D., specializing in psychiatry, carried out his thesis research in the early 2000s on how to enlist community members in helping former child soldiers in Nepal recover from the trauma they had experienced. Kohrt knew that it would take more than a few trained psychiatrists like him to solve the growing mental health struggles of people in developing countries around the world, where mental health resources are scarce and stigma against mental diseases is rampant. But he thought if he could recreate the kind of supportive, empathetic, non-judgmental environment he’d seen at the healing temple in other places, communities could become better at helping those with mental health issues.

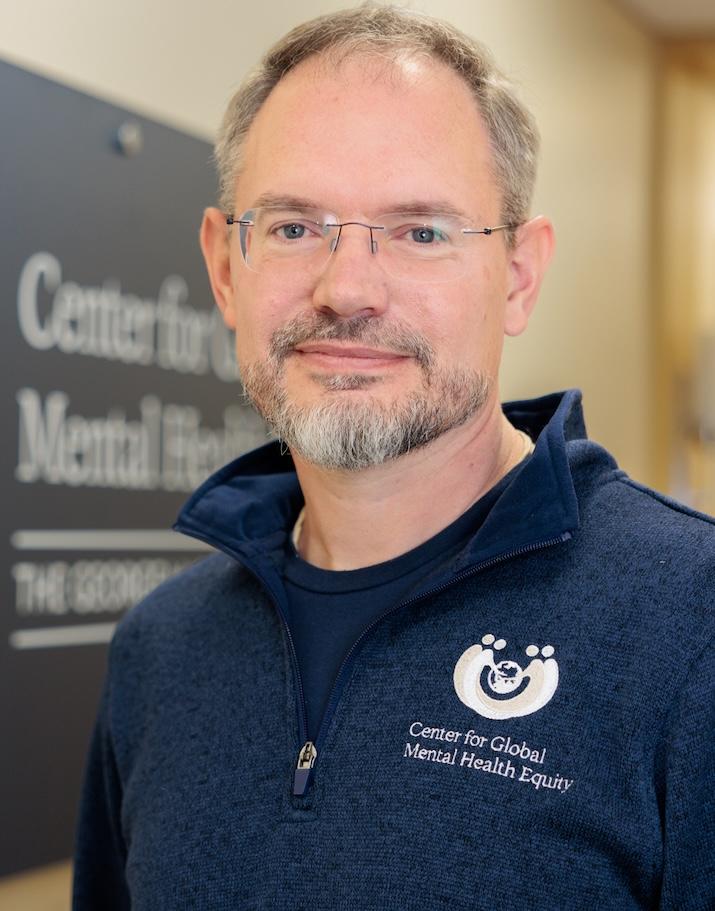

Today, Kohrt directs the GW Center for Global Mental Health Equity, which leads worldwide efforts to improve mental health training for people not typically experienced with delivering therapy or formal mental health support. The National Institutes of Health, the World Health Organization (WHO), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and others have funded his work. Kohrt and his colleagues believe that, with the right tools, community health workers, volunteer aid workers at refugee camps, teachers, police officers, social workers and others can be vital players in identifying and treating mental illnesses—and easing the worldwide burden of psychiatric diseases.

“I want to break down the divides between the healer and the healed,” says Kohrt, the Charles and Sonia Akman Professor of Global Psychiatry in GW’s School of Medicine and Health Sciences. “The goal is that in some ways everyone can be a healer toward others and, on the flip side, everyone should feel comfortable reaching out to those around them when they need support.”

“I think it’s incredibly problematic that we have this idea in our heads that only when you’ve been trained for years and have all these degrees can you really understand someone’s emotional experience.”

– Brandon Kohrt, Charles and Sonia Akman Professor of Global Psychiatry

Alleviating the Global Burden

More than 80% of people worldwide who have mental health conditions live in low- and middle-income countries. Exposure to war, poverty, political upheaval and natural disaster in these places often leads directly to higher rates of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, yet these nations have the fewest mental health resources.

According to the WHO, less than a quarter of all people with depression in low-income countries ever receive adequate treatment—mostly because of provider shortages. A handful of countries in Africa and Asia have less than one psychiatrist per million people, and even in urban areas with higher concentrations of trained professionals, cultural norms, religious beliefs and long-held stigmas can prevent people in need from seeking help.

Despite these dismal statistics, Kohrt made an observation as he traveled around the world, and it became a kind of mantra for his career: Everyone has the potential inside them to help heal other people’s distress.

“I think it’s incredibly problematic that we have this idea in our heads that only when you’ve been trained for years and have all these degrees can you really understand someone’s emotional experience,” says Kohrt. “It really devalues the fact that actually many people, with the right support, can be incredible healers and have a very strong emotional connection and understanding of others.”

Kohrt’s research began to focus on efforts to boost the capacity of community members in places experiencing war, poverty and natural disaster to provide mental health support to those around them.

Byamah Mutamba, a senior psychiatrist at Butabika National Referral Mental Hospital in Uganda and a long-time collaborator of Kohrt, says that training people already immersed in communities to help triage mental health struggles can help ease the burden on providers like him. His 600-bed hospital, located in the capital city of Kampala, is a referral hospital meant to handle large volumes of patients referred from smaller hospitals and clinics. But even its resources are stretched. The hospital usually has more than 1,100 patients, Mutamba says, and is staffed by just 13 psychiatrists. (Uganda has one of the lowest rates of psychiatrists in the world, at just one per million people.)

“We need earlier intervention when it comes to mental health care,” he says. “We’re sitting downstream at the referral hospital waiting for all the problems to arrive, and we’re very, very overburdened. Community health workers are a good upstream resource that can help prevent some of the problems from getting to us.”

In Uganda, Kohrt, Mutamba and Sauharda Rai, a research scientist at the GW Center for Global Mental Health Equity, have been trying to do just that—training community health workers to provide basic mental health treatment in the home, in the community and at primary health facilities through a project supported by the Wellcome Trust.

Equipped to Heal

At the time Kohrt began to look at training non-specialists, many non-governmental aid organizations were already boosting their efforts to give social workers and aid workers more mental health skills. But their programs varied drastically in effectiveness. Kohrt saw an opening to help, by creating a tool that would gauge how well-trained community workers were in providing mental health services.

The resulting toolkit, now called EQUIP (for Ensuring Quality in Psychosocial and Mental Health Care), includes a set of role play exercises in which people being trained are tested to see how effective they are at skills like showing empathy, using non-verbal communication, providing feedback to patients, and reflecting on and reframing their patients’ problems. The end goal of EQUIP is not just to ensure that non-specialists are well-trained before they begin working with patients on mental health struggles but also to provide feedback to the organizations carrying out the training on how to improve.

Rozane El Masri, a research coordinator with the non-governmental organization War Child, used EQUIP while training non-specialists to support teenagers affected by armed conflict in Lebanon. “EQUIP enables trainers to really zoom in on what our trainees need. We understand what areas we need to focus on during training and tailor our sessions accordingly,” she told the WHO in 2022.

In early pilot studies in Lebanon, Peru and Nepal, community health workers and other providers who were taught psychological interventions using EQUIP had better helping skills after just two weeks of mental health training compared to providers taught without the EQUIP platform. Studies in other countries have confirmed how well EQUIP assesses the skills of trainees and leads to better-prepared mental health workers.

Today, Kohrt estimates that EQUIP has been used in more than 1,000 trainings across 37 countries. The toolkit is freely available through the WHO, so any organization can use it. Kohrt’s team at the GW Center for Global Mental Health Equity currently helps interested trainers and program managers get started using EQUIP.

Mansurat Raji, a GW researcher who works closely with Kohrt on EQUIP, has traveled around the world helping with these efforts. She says the most rewarding part of the program is seeing the difference it makes for people who finally have access to mental health support.

With Raji’s help and the incorporation of EQUIP into mental health interventions developed by others, the non-governmental organizations Grow Strong Foundation and Transcultural Psychosocial Organization Nigeria trained their aid workers to carry out informal counseling sessions with caregivers in Nigerian refugee camps at the same time they improved the infrastructure—building playgrounds and establishing nutrition and education programs for children.

Many people in the camps had experienced severe violence, upheaval and loss due to years of armed conflict that has led to more than two million displaced people in the northeast of Nigeria. Before the intervention, children and their mothers often sat silent and alone, interacting with few people around them. Most were wary to ask for advice or help from anyone working in the refugee camp.

“The change after the program was implemented was incredible,” Raji remembers. “You saw kids starting to play again and to speak with each other. The mothers said that for the first time they felt safe talking to the health workers and the staff.”

When adults who participated in the programs were asked whether their mental health and well-being had improved, 97% said yes.

Kohrt and the team at the GW Center for Global Mental Health Equity help trainers and program managers get started using EQUIP, which has been deployed in countries around the world through more than 1,000 trainings.

Mansurat Raji and the GW team give a presentation in Budapest, Hungary on the Mental Health and Psychosocial Support - Minimum Service Package, a resource for humanitarian actors.

Fighting Stigma

Even when community health workers can be trained to recognize psychiatric diseases, provide basic levels of support and refer patients to get treatment, there is a large hurdle that often remains: stigma.

On one of his earliest trips to the Nepali healing temple, Kohrt recalls a man who—thanks to the support of the priests—saw an improvement in the severe mood swings he had been having. But when the man returned home, he was still shunned by his family, who believed he was cursed.

In most of the developing world, stigma against mental conditions is rampant—20 countries including Bangladesh, Uganda and Kenya still criminalize attempted suicide. Even trained health care providers often discriminate against those with psychiatric diseases, believe that mental illness is incurable or prefer not to work with those struggling with mental health conditions.

“The stigma works in a lot of directions,” says Rai. “People don’t seek mental health care because they don’t want to be stigmatized by their community and their family but also health care workers carry their own personal stigma. They might not want to work with patients who have mental health problems because they may think they’re violent, for instance.”

Sauharda Rai (bottom left) with community health volunteers in Nepal.

Kohrt, Rai and their colleagues are changing that. Recently, in collaboration with the Transcultural Psychosocial Organization (TPO Nepal), they created a program called RESHAPE (Reducing Stigma among Healthcare Providers) that involves integrating people with lived experience of mental illness into mental health training sessions for community health workers.

“It’s important for them to see the real humans behind what they’ve been learning about,” says Rai.

Kohrt’s group found that when patients spoke with community health workers in Nepal during mental health care training, the health workers not only scored lower on a scale of stigma but also became more accurate at diagnosing mental health conditions. He thinks that is because they rely less on memorized checklists of symptoms and more on the nuances of a person’s experience as they think about what they are struggling with.

As part of RESHAPE, Kohrt and Rai have adapted a technique called PhotoVoice to help patients step into the role of advocates, sharing their stories through a series of photographs and spoken word.

PhotoVoice helps those struggling with a mental health condition document and share their stories through a series of photographs and spoken word. The approach helps to reduce stigma among health care workers by building empathy and greater understanding about a person's condition.

In one PhotoVoice series, a Nepali man who is in recovery from alcohol use disorder clicks through photos of the local store where he spent his entire paycheck on alcohol, the bridge that he stumbled drunkenly over, and the community health workers who finally diagnosed him and helped him recover. In his last photo, he shows a beautiful and intricate ceiling mural that he painted of clouds and birds when he was able to return to his vocation as a painter.

“He says that when he was living in the throes of alcoholism, his hands shook so much that the most he could paint was a single color on a wall,” Kohrt recounts. “But because of this treatment he can create art. And that story really resonates with the health care workers who hear it.”

Today, RESHAPE and PhotoVoice have been expanded into studies in China, Ethiopia, India, Tunisia and Uganda, and the team has developed a freely available manual on it.

“People don’t seek mental health care because they don’t want to be stigmatized by their community and their family but also health care workers carry their own personal stigma.”

– Sauharda Rai, Research Scientist with the GW Center for Global Mental Health Equity

A Crisis Closer to Home

For decades, Kohrt optimized his community-based mental health care approach for the developing world, where shortages of trained professionals are especially dire. But higher income countries like the U.S. are also facing a mental health crisis, with rising rates of depression, anxiety, suicide and substance abuse over recent years.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, more than one in five U.S. adults live with a mental illness, and 570 counties across the U.S. are considered “mental health care deserts,” with no psychologists, psychiatrists or counselors. When rates of mental health challenges increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, drawing new attention to the problem, Kohrt and his team wondered if mental health care strategies they’d developed and validated in other countries could be applied closer to home.

In 2021, Kohrt received a five-year, $3.5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to bring his training strategies to underserved populations in New York City. There, his team, in collaboration with the New York City Mayor’s Office of Community Mental Health, is working with organizations that provide youth mentoring, job training, housing assistance and other public welfare efforts.

“Imagine you’re someone working in a housing assistance office,” says Kohrt. “Your clients regularly come in to meet with you and fill out paperwork, and you might notice that one of them is really struggling. They’re perhaps too anxious to get their forms filled out. What can you do to help reduce their distress?”

Kohrt and colleagues are using a brief five-session intervention called Problem Management Plus (PM+), originally developed by WHO researchers and tested previously by Kohrt’s team in Nepal. In PM+, community workers or volunteers take a two-week class to become a PM+ helper. Kohrt’s team collaborated with Adam Brown, an associate professor of psychology and head of the Trauma and Global Mental Health Lab at the New School in New York City, to adapt the training to a part-time format for 12 weeks over Zoom. The ultimate goal of PM+ is not to have the trained helpers offer treatment for a specific disorder but to enhance their ability to help people who are struggling with their mental health.

“I’d say it’s like a soft introduction to therapy,” says GW senior research associate Chynere Best, who is on the New York City PM+ team. “We want you to be able to sit with a client for a dedicated period of time and work through a specific problem that the client is having.”

In developing countries like Nepal, studies have already shown that PM+ can significantly reduce psychological distress and depression symptoms. Best says data on whether those results hold true in a high-resource country like the U.S. are still being collected, but she has heard positive feedback from the organizations involved. One case worker at a low-income housing facility told Best she was skeptical that the course would be useful. But since finishing PM+ training, she’s been able to help clients better cope with challenges. For example, one client explained that the deep breathing exercises learned in PM+ sessions were helpful in controlling their anger.

Members of the GW Center for Global Mental Health Equity, from left to right: Sauharda Rai, Mansurat Raji, Chynere Best and Brandon Kohrt.

So far, Best and Kohrt have worked with 39 different organizations across all five boroughs of New York City to integrate PM+ into their social support efforts. But the team is already thinking bigger—they’d like to expand the program to other U.S. cities, including Washington, D.C.

“What we want is to integrate psychological skills into other daily things that people are doing, whether that is a community health worker providing postnatal care in Pakistan or a social worker in New York City,” says Kohrt.

Wherever Kohrt’s work brings him, he remembers what he first learned at the Nepali temple more than 30 years ago: Small shows of support and acts of kindness from the community around them can go a long way in easing people’s distress. For people around the world to embrace this idea will take a shift in ideas about mental health, a reduction of the stigmas surrounding mental health, and efforts to spread the training of mental health support skills. Slowly, he says, those things are beginning to happen. Recently, organizations in Gaza and Ukraine have begun using EQUIP to assess their mental health training efforts.

“Mental health seems like an insurmountable problem so it’s easy to get demoralized,” Kohrt says. “But as I see more and more people get interested in solving these challenges, it really creates hope for the future.”